In the News

Stories from the community

Robarts Library at Fifty

How Fort Book Became the Campus Living Room

September 26, 2023

By: Geoffrey Vendeville

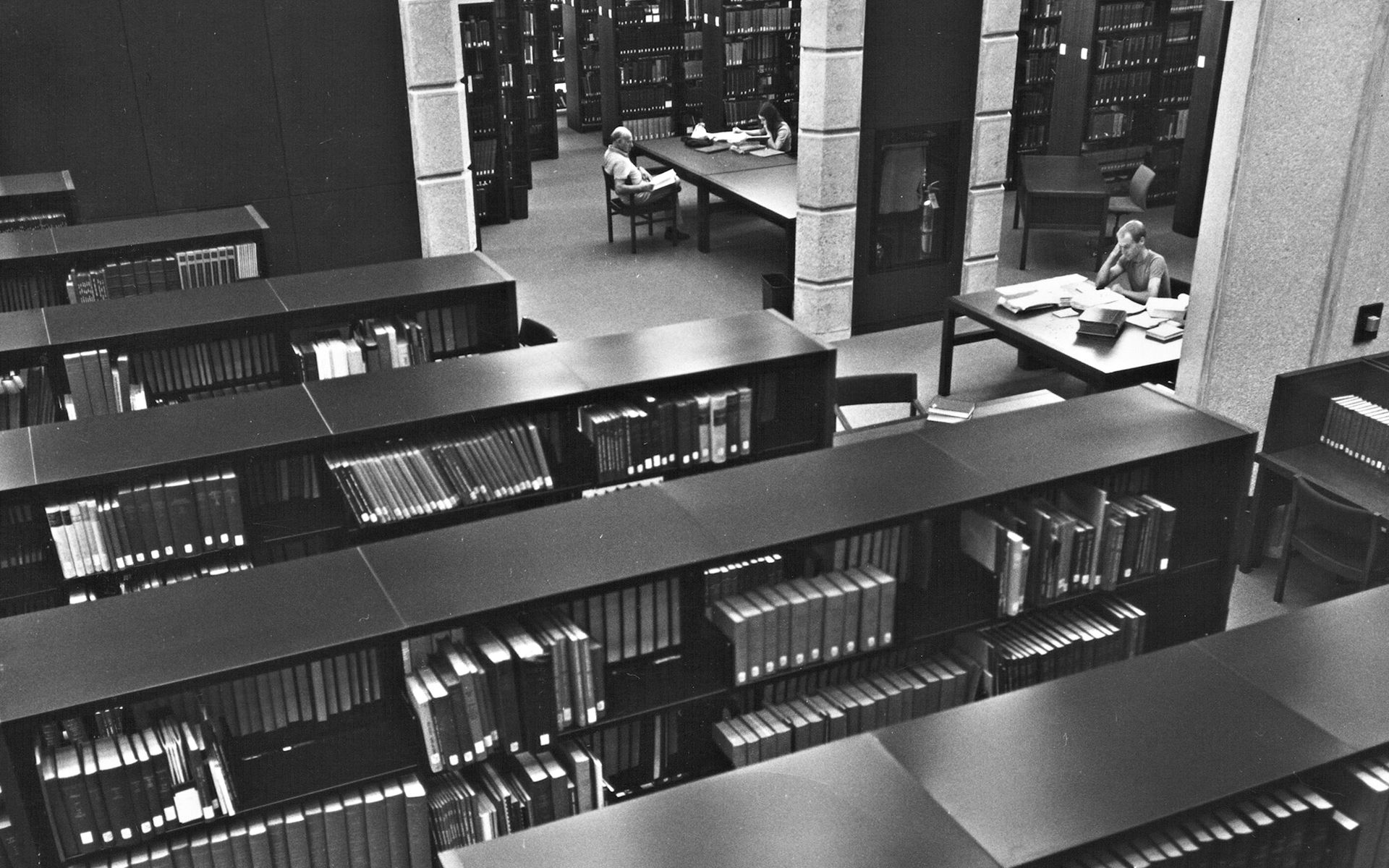

In September 1973, the University of Toronto’s campus weekly, The Varsity, greeted students with a front-page photograph of John P. Robarts Library, the new, impossible-to-miss concrete giant on St. George Street. “Welcome to U of T and Fort Book,” the headline shouted.

Robarts’ half-centennial has provided an opportunity to reflect on its past – and look towards its future. An exhibit on the main building’s ground floor traces Robarts’ history, with displays focusing on architecture, technology and social movements that shaped the library’s evolution. The exhibit includes alternative design plans for the library, archival photos and a film still of Robarts as re-imagined by the makers of Resident Evil: Afterlife. A virtual retrospective and more in-person events are being planned to commemorate the anniversary.

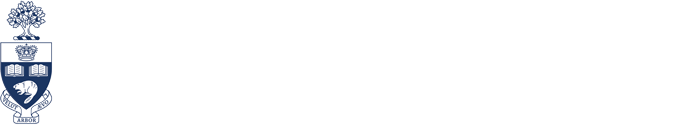

Originally built to house 2.7 million volumes and accommodate 4,100 people in reading rooms and study carrels, Robarts was the largest academic library building in the world, intended to make room for U of T’s growing library collection and the influx of students born during the Baby Boom. U of T President Claude Bissell, who played a central role in its construction, called it “the final, climactic stage in the development of the higher learning at the University of Toronto.” The triangular library complex included the School of Library Science and what is now the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. The building’s namesake, Premier John Robarts, said the buildings – which came with a $41.7-million price tag – should not be judged based on cost, “but in terms of how many people would pass through them over the next fifty years.”

Cover of The Varsity newspaper from September 12, 1973 (University of Toronto Archives)

Cover of The Varsity newspaper from September 12, 1973 (University of Toronto Archives)

Then President Claude Bissell pictured with a model of Robarts Library, 1970 (University of Toronto Archives)

Then President Claude Bissell pictured with a model of Robarts Library, 1970 (University of Toronto Archives)

Now, as many as 18,000 people visit Robarts in a single day, while countless more access its collection online. The index card catalogue and coat check for visitors are long gone, but Robarts is now home to spaces for 3D printing, meditation, and mindfulness – even a family study room designed for parents and children, the first space of its kind in a Canadian academic library. Although the U of T Libraries collection contains more than 11 million physical items in total, it now mainly acquires electronic material and hosts data centres with a storage capacity of 1.5 petabytes.

Although the library’s layout and especially technology have changed dramatically, its role remains the same: to support research, discovery and community, said Chief Librarian Larry Alford. “When Robarts Library opened, it was very much seen as a place for students – and faculty, but especially students – to come together to study and work together,” he said. “That hasn’t changed at all. I think it’s as important now as it was in 1973.”

To create much-needed study space, the library recently underwent its first expansion in 42 years with the addition of a free-standing, five-storey building on its west side. The project was made possible through the generous support of the late Russell and Katherine Morrison, along with a thousand other donors. Katherine, who earned a PhD in English in 1979, was among the first generation of students to use Robarts Library and recalled “practically living” there during her graduate studies.

Robarts Common came equipped with 1,200 new study spots – a 25 per cent increase – including soundproofed rooms with big-screen TVs for group study. Although officially unveiled last fall, it became popular with students even before its formal opening, Alford said.

“In the spring, we unlocked the doors but didn’t want to make a public announcement because there was still some work going on, but by the afternoon it was completely full,” he said. “The students basically let each other know and completely filled it up. It was really quite amazing to me.”

Robarts Common and Robarts Library September 2023 (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

Robarts Common and Robarts Library September 2023 (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

Group of students engaging in conversation on the second floor of Robarts Common (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

Group of students engaging in conversation on the second floor of Robarts Common (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

Three students relaxing and laughing in Robarts Common (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

Three students relaxing and laughing in Robarts Common (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

Birdseye view of the second-floor lecture-style desks at Robarts Common (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

Birdseye view of the second-floor lecture-style desks at Robarts Common (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

In the realm of technology, Robarts Library was a centre for innovation. Under the leadership of Robert Blackburn, chief librarian from 1954 to 1981, U of T Libraries became an early adopter of an automated catalogue. Ritvar Bregzis, head of the libraries’ cataloguing department, led the transition away from handwritten index cards to machine-readable records that could be shared with other libraries. He collaborated with Professor C.C. (Kelly) Gotlieb, the director of the Institute of Computer Science, who helped the library acquire its first computer – a Sigma 7 – in 1969. Robarts discontinued its printed card catalogues in favour of microform in 1976, four years before the U.S. Library of Congress. Though not the first institution to have a computer-output microfilm catalogue, Robarts was the first large research library anywhere that had converted its entire catalogue, Blackburn said. “Our pioneering in the field was not unnoticed or unappreciated,” he wrote in Evolution of the Heart, a history of U of T Libraries. The first online catalogue, “Felix,” came into service in 1987.

Today, Robarts Library supports digital scholarship including in the field of non-destructive analysis of ancient books. Hidden Stories – an interdisciplinary project involving the library, the Old Books New Science lab led by Professor Alexandra Gillespie and U of T Engineering – seeks to uncover historical insights by examining the physical properties of ancient volumes, using techniques such as atomic force spectrometry. Many of these books are too fragile to open, let alone peruse. “They carry information about the people who came before us, to us,” Gillespie, U of T Vice-President and Principal of U of T Mississauga, told CBC. “They were deliberately designed to do that, to take knowledge across time and place. They do that with text and they do that with drawings, but as objects themselves they do it too.”

Jesse Carliner, a user services librarian and co-curator of the Robarts Library exhibit with university archivist Tys Klumpenhouwer, said technology was not the only important driver of change at the library – so, too, was the U of T community

“The library has evolved from being this very formal, book centre to being more of a socially oriented student centre,” Carliner said. “It went from being an imposing concrete monolith to kind of the campus living room.”

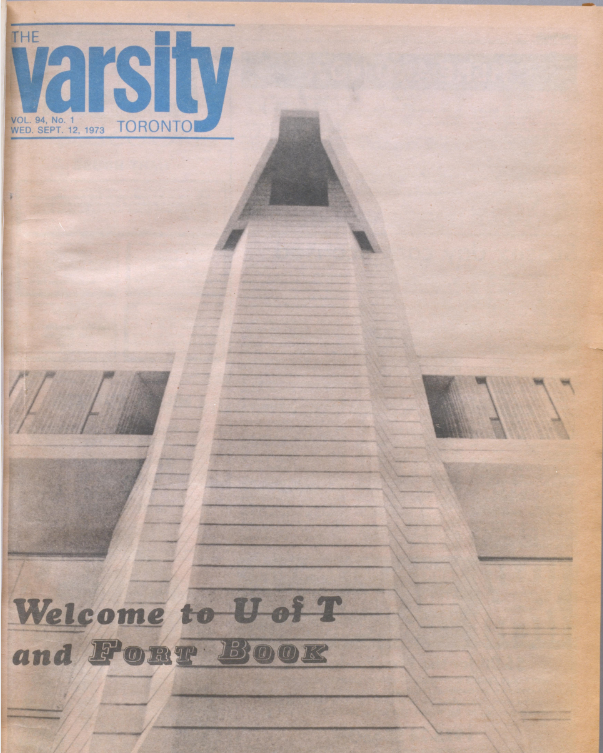

While initially only faculty and graduate students were supposed to be granted access to the bookstacks, undergraduate students staged protests, including a sit-in at Simcoe Hall, to open the stacks to everyone. The library has continued to reshape itself to become more welcome of the whole academic community, through the addition of prayer rooms, an ablution room for Muslim students and 2SLGBTQ+ events. Just last summer, Fisher Library hosted Raymond Frogner, head of the archives at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, for a talk about confronting historic biases and promoting Indigenous knowledge within library collections.

Though Robarts Library has undergone many changes, the debate around its imposing concrete exterior remains as lively as ever. Designed by the New York firm of Warner, Burns, Toane and Lunde, in association with Toronto-based Mathers and Haldenby, the brutalist landmark divided opinion from the start, with architect Ronald Thom saying it “represents everything in architecture that is arrogant and wrong.” It has been compared to everything from a “giant chess piece” to a “sci-fi version of a medieval castle.” But for the building’s many critics, there seems to be an equal number of admirers. Italian author Umberto Eco described it as a “masterpiece of contemporary architecture” and, more recently, Robarts topped Monocle’s list of architectural must-sees in its Toronto travel guide.

Although Chief Librarian Alford sees why the building’s architecture is controversial, he has always been a fan. “If you look inside the building, as I’ve often done, you stand on the second floor and look up, you can’t help but be impressed and it becomes clear that the architects paid a lot of attention to every detail,” he said.

Escalators in the main atrium of Robarts Library (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

Escalators in the main atrium of Robarts Library (Photo by Hanna Borodina)

If you look inside the building, as I’ve often done, you stand on the second floor and look up, you can’t help but be impressed and it becomes clear that the architects paid a lot of attention to every detail

Even decades later, Robarts stands out against the backdrop of non-descript office buildings and crystalline condos. As a U of T graduate student put it in an open letter to the Toronto Star not long after Robarts opened: “It soars, it’s interesting, and most importantly, it doesn’t look like everything else in Toronto.”

As for what the library and its role will be 50 years from now, Alford said it’s impossible to predict. In the 1940s, when microfilm came into use, many academic librarians speculated print would become obsolete. Alford said the libraries of the future are likely to play an increasingly important role in AI-assisted analysis and authentication of information, but beyond that it’s anyone’s guess.

“If you think about the radical changes over the last five decades, I don’t think any librarians could have said where we were headed.”